Introduction

The end of capitalist globalization marked the rise of racist right-wing populism around the world. Turkey and the long history of racism in Turkey make a model case for tracing different racist ideologies that are prevalent all around the world today. A poll from 2015 showed that only 9% of people from Turkey believe that the atrocities inflicted on Armenians during World War I should be labeled ‘genocide’ and require an official apology (Arango 2015). In 2019, after the expansion of Turkish invasion of Syrian Kurdistan through ‘Operation Peace Spring’ (which was aimed to replace the ‘terrorist’ Democratic Union Party(PYD)and Kurds in the region with a ‘safe-zone’ and the Syrian Arab Refugees in Turkey), president Erdoğan’s popularity rose by nearly 4% (Birgun Gazetesi 2020). In the last decade, homes and houses of prayer of Alevis were targeted by multiple attacks. In 2018 and 2019 #ÜlkemdeSuriyeliİstemiyorum (#IDoNotWantSyriansInMyCountry), trended on twitter and multiple lynching attempts against Syrian refugees took place since 2018.

None of these racist acts were new for the country. Turkey has a long history of racializing people who are not Turks, Muslims, and Sunnis. However, whenever politicians, academics, or anyone else criticizes this, they are declared traitors to the nation and allies of the enemy by the country’s ultra-nationalist media and ruling class. Hence, because particularistic approaches to Turkish racism are often dismissed, it is important to consider the development of “Turkishness” within a comparative context through a theory of development of racial discourses. This theory I sketch out in the first section of this paper ties the origins of race directly to the crises of pre-capitalist regimes, and the transition from pre-capitalist modes of production to capitalism.

It is important to clarify what one means by race before we explore its history in a specific context. Race is an ideology that is used to separate individuals into different cross-class social categories within the political economy. Ideology is:

… best understood as the descriptive vocabulary of day-to-day existence, through which people make rough sense of the social reality that they live and create from day to day. It is the language of consciousness that suits the particular way in which people deal with their fellows. It is the interpretation in thought of the social relations through which they constantly create and re-create their collective being, in all the varied forms their collective being may assume: family, clan, tribe, nation, class, party, business enterprise, church, army, club, and so on. As such, ideologies are not delusions but real, as real as the social relations for which they stand. (Fields 1990: 110)

Race and racialized ideologies perpetuate their own continuous reproduction, so long as the social conditions that led to their acceptance continue to exist. However, only under capitalist relations of production racial essentialism becomes widespread, as capitalism continuously differentiates workers.

Racial ideologies are expressed through race discourses. Race discourses develop in pre-capitalist economies as race war to explain revolts against the sovereign absolutists. Under capitalist colonization of non-capitalist regions, systematic theses of race emerge to explain why these regions need “improvement.” Once capitalism is established, racism systematically explains the racialized division of labor that developed historically. Racism, unlike previous forms of racialized discourses, essentializes differences between social groups.

In the case of Turkey, throughout the entire Ottoman period, we see the continuous changes in the axes of the race war. However, these changes in racial notions are used pragmatically, rather than systematically, by the ruling classes. During the last decade of the Empire, we see the systematic use of racialized knowledge for the first time by the state, ruled by the Young Turks, to develop a Muslim bourgeoisie. These efforts initially fail as the Empire disintegrates; however, they are revitalized by the founders of the Turkish Republic, this time specifically oriented towards the development of a Turkish-Muslim bourgeoisie. I argue that this is the period within which theses of racism become systematic and the notion of improvement comes to the forefront. The rulers of Turkey, much like the rest of the world, try to tie race to biological and linguistic characteristics throughout the early republican period. However, until market dependence becomes the dominant form of social reproduction, assimilation into Turkishness is still possible. Only in capitalist Turkey, since the 1990s we see the essentialization of Turkishness.

This paper is a study of racialized ideologies throughout the transition from feudalism to capitalism. The theoretical framework is developed through the evolution of race in the western world and applied to the Ottoman/Turkish case. The applicability of the categories is still open for question as the axes of racial division are unique in each case. However, if there is a generalizable theory of the origins of capitalism, there must be a generalizable theory of the origins of racial essentialism.

Race and Capitalism

Racial ideologies appear in three distinct ways as societies transition from pre-capitalist modes of production to capitalism. First, in the feudal era the notion of race war emerged in reaction to the Roman ideology of sovereignty (Foucault et al. 2003: 65-85). The ideology of race war was necessary to unify the lords and the peasants against the sovereigns who had absolute power, as both classes had a vested interest in fixing or removing their tax burdens to the sovereigns. In this period, sovereignty was no longer viewed as unifying the monarch and his subjects; as Foucault puts it, sovereignty “does not bind; it enslaves” (Ibid: 69).

The Malthusian population crises under pre-capitalist developmental regimes created the preconditions for intensification of class conflict against absolutist sovereignty, given that rents and taxes were the primary mechanism for exploitation of the subjects by the sovereign (Brenner 1985). This explains why the ideology of race war appears in the late medieval period. In this period, both the lords and peasants wanted to increase their share of the total product, as political accumulation and pre-capitalist colonization reached their initial limits for sustaining the social reproduction of the existing classes under the crisis of feudalism. The necessary political and military conflicts, both against the sovereign and against other lords (as the only way for lords to increase their surplus was gaining political control over more fertile land), had to be justified to the peasant populations on the basis of ethnic, cultural, religious, linguistic or other types of differences. So, the race war began. However, there were no coherent systematic thesis about different races. As Foucault puts it:

Even in the Middle Ages, we find phrases like this in the chronicles: “The nobles of this country are descended from the Normans; men of lowly condition are the sons of Saxons.” Because of [these] elements … conflicts— political, economic, and juridical—could … easily be articulated, coded, and transformed into a discourse, into discourses, about different races. (Foucault et al. 2003: 101)

This meant that as the social property relations and the dynamics of political accumulation begun to be transformed throughout Europe, so did the vocabulary of race war that was used to describe the conflicts that shaped these transformations. However, races in this sense did not have coherent definitions, and instead they were used pragmatically for the purposes of political and economic domination.

After agrarian capitalism was established in England and capitalist relations of production incentivized the geographic expansion of the market both within and beyond England, the flexibility of the race war enabled it to evolve into the racialized ideology of improvement. In this period, history became the man’s struggle for progress from the state of nature to a “civilized state” (Locke 1960). The state of nature represented the absence of capitalists social property relations and a capitalist state (Tuckness 2020), where there was no market compulsion for continuous development of the productive forces, and the direct producers maintained direct access to land for their own subsistence (Brenner 1985). In England, the ideology of improvement initially emerged as a defense of the enclosures, as the mass consolidation of land in the hands of agrarian capitalists(Žmolek 2013:115), and the market compulsion to continuously develop the forces of production (Brenner 1985) enabled the growth of agricultural output. This improvement was weaponized to dispossess small peasants in the English countryside.

Throughout the colonization of Ireland, as English capitalism expanded, the notion of improvement was racialized in a systematic way for the first time. William Petty suggested the Irish lived in a state of nature as “wretched Cabin-mens, slavishly bred” (Cited in Bhandar 2018: 42). For Petty, the inferiority of Irish people drove the low productivity and valuation of Irish land. This meant that Irish land required improvement through “the settling and anglicizing of the Irish population,” or in short, through colonization (Ibid 43).

Similarly, in the American colonies, John Locke argued that “there must of necessity be a means to appropriate [lands] some way or other, before they can be of any use, or at all beneficial to any particular man” (Locke 1960: 209). For Locke, appropriation of private property was what enabled identification of the individual with that property which forms his essence (Balibar 2002). Hence individuals can only become “man” in a Lockean sense through the appropriation of private property, which constitutes their historical identity. This meant that the “savages,” who lived in the state of nature without clearly defined property rights, had no history and only existed in a static pre-civilizational condition where they waited for their lands to be appropriated by industrious man (Bhandar 2018: 170). Hence in the cases of the colonization of Ireland and North America, we see the racialization of the notion of private property and use of the discourse of improvement to justify the dispossession of those who are deemed inferior based on the standards of agrarian capitalist production and social property relations. The discourse of improvement is the earliest systematic approach to systematically construct races to justify capitalist colonization.

Colonization and enclosures drove the expansion of the latent segment of the reserve army of labor and pauperism, as dispossessed farmers now could now only survive through working for capitalists. After their dispossession, the extreme poverty and misery of the newly transformed proletarians became racialized in the colonies, while the struggles of the native English workers enabled them to gain legal political rights (Fields 1990: 103). Given that racial discourses of improvement were already utilized in the process of the creation of the proletariat through capitalist colonization, the discourses of the “Indian savage,” the “slavishly bred” Irish and others were readily available to justify the disproportionate poverty, or unequal legal political situation of racialized workers in the colonies. However, in each case the chronic shortage of labor in the early American colonies, the inability of the colonists to press the natives into labor sufficiently, and the failure to increase the rate of exploitation of Irish and African and other tenant farmers due to their successful resistance struggles during the tobacco crisis of late 1660s and 1670s, required new forms of “unfree” labor in the American colonies (Ibid 104-106).

The indigenous peoples and the Irish were viewed inferior to “civilized man” throughout their colonization; but since they made up the majority of the population in their respective colonized nations, the colonists had to engage in pragmatic legal-political relations with them . As Barbara Fields puts it. “A colonial ruler does not just want the natives to bow down and render obeisance to their new sovereign” (Ibid: 112) The natives must cooperate with the colonists in order for the colonists to tax, employ, recruit and exploit them continuously. This was not the case for the African and Afro-Caribbean slaves. Racism, emerged as an ideology to justify the legal unfreedom of black slaves through the essentialized differences between races (Fields 1990; Post 2017). Race and racism in this sense differs from previous ideologies of race war and improvement in the sense that the inferior races cannot gain legal-political equality in a formal sense, as the Irish and Indigenous peoples in America could. As Charlie Post describes:

The notion of race arose to explain and justify slavery and other forms of bondage in societies where legal freedom and equality was becoming the norm. In societies before capitalism, where exploitation takes place through non-economic coercion, inequality was assumed to be the ‘natural’ condition of humanity. Only with capitalism, where exploitation takes place through the ‘dull compulsions of the market,’ can the notion of legal-juridical freedom and equality become the ‘common sense’ of society. Put simply, it is only with the development of capitalism that race becomes a necessary means of explaining and justifying inequality. (Post 2017)

The transatlantic slave trade existed prior to capitalism. The discourses required to justify non-capitalist forms of slavery however differ from racist discourses of capitalist slavery. These are effectively in the same category as the pre-capitalist discourses of race-war as they were used non-systematically to justify the domination of one group over another.

Racism under capitalism, however, differs from this in the sense that it systematizes the theses of racial inferiority, integrates them into the structure of capitalist political economy, and systematically reproduces and reinvents races in order to explain colonization, legal-political inequality, or the racialized division of labor, all on the bases of essentialized differences. The notion of race and races in this period came to describe “no longer a battle in the sense that a warrior would understand the term, but a struggle in the biological sense: the differentiation of species, natural selection, and the survival of the fittest species” (Foucault et al. 2003: 80). In this sense, the discourse of ‘improvement’ was the transitional discourse from race-war to racism, as it was the first attempt to systematize racial discourses to serve the needs of capitalist colonization.

After the abolishment of slavery, and as unfree forms of labor moved to the peripheries of capitalist division of labor, racism survived. This was because the expansion of the capitalist division of labor through colonization, mass migrations caused by primitive accumulation, and the persistence of unfree forms of labor permanently racialized the division of labor under capitalism.

The dynamics of capitalist competition continuously differentiates the workers through the profit differentials between and within industries (Botwinick 2018). Under this dynamic, the racialization of employment and wage disparities between different races flowed naturally from the racialization of management of land and labor through capitalist colonization. As Roediger puts it

As members of both a white settler and a slaveholding society, Americans developed a sense of themselves as white by casting their race as uniquely fit to manage land and labor and by judging how other races might come and go in the service of that project (Roediger 2017)

This racialization of management is common in most capitalist countries, as positions of management usually require citizenship as well as racial, ethnic, and religious assimilation into the dominant racial categories. As capitalist management became more scientific throughout the late 19th and early 20th century, racial knowledge was integrated into scientific management and often took biological forms (Ibid). Racism was used to improve profitability through the differentiation of workers (Roediger and Esch 2014). Hence even as different races gained legal-political equality, their positions within the political economy were justified through racial discourses in labor management.

The discourse of essential differences (biological, cultural, religious etc.) between workers of different races, or racism, in the absence of strong institutions of interracial class solidarity, becomes the hegemonic discourse which explains economic disparities between workers and further weakens the possibility of interracial solidarity (Brenner and Brenner 2016). This is the form of racism we witness most commonly in today’s world among workers, as the notion of poverty is racialized globally as well as within every capitalist country. Racism allows capitalists to differentiate workers to increase profitability, and enables workers identified with the dominant race to improve their material conditions of existence through opting into their race at the expense of other races.

We have explored the three different discourses of race from feudalism to capitalism. In the feudal period, the discourses of race appeared in reaction to sovereignty and in the form of race-war. These discourses were not systematic and were weaponized for pre-capitalist forms of political domination and accumulation. The expansion of capitalism through capitalist colonization required the first systematic theses of race. However, these discourses did not essentialize differences since the colonists still needed to engage in political-legal relations with the colonized. Only after the emergence of slavery, we see the essentialization of racial differences and their integration into the political economy. During slavery, racism justified the legal unfreedom of the black slaves. After, the abolishment of plantation slavery, and with the decline of unfree forms of labor, racism – in the form of essentialized differences between distinct groups – became the hegemonic discourse for justifying and describing the racialized division of labor. Capitalists utilize racism to increase profitability through racialized scientific management and differentiation of workers. Workers opt-in for race and racism in the absence of strong institutions of interracial class solidarity, as it appears easier for them to defend and improve their material conditions through race than through class struggle.

These three categories of discourses help describe the history of race discourses in modern Turkish history. I categorize the Ottoman period as the period of race-war. The axes of the race-war went through multiple evolutions since the beginning of the 19th century as the non-Muslim and non-Turk populations reacted against their Ottoman sovereign. The Republican period 1925-1950 is where we see the rise of the ideology of improvement alongside race-war, as the projects of Kemalism and Republicanism aimed to modernize Turkey. However, improvement in the Turkish context was not fully capitalist due to the non-dominance of capitalist social property relations, and the dependence of the Republican state on small Anatolian farmers as a political base. Until market dependence became the dominant relationship for social reproduction, assimilation into Turkishness was possible. As Turkey transitions into capitalism in the last few decades, we see the rise of racism which justifies legal-political inequality and the racialized division of labor.

Ottomanism and Islamism

The Ottoman Dynasty was found in a “frontier proximity in the Christian world” which “kept its military and religious fervor at full pitch, when other emirates in the hinterland lapsed into relative laxity… The [Ottoman] rulers from the start conceived themselves as ghazi missionaries in a holy war against the infidel” (Anderson 2013: 363). The ideologies of political accumulation maintained Islamic character in the form of race-war as the dynasty continued to expand.

As the expansion continued to the Balkans in the West, Crimea, and Caucuses in the North, where the majority of the populations were non-Muslim, there were no attempts at systematic mass conversion based on the Islamic ideology of tolerance. Instead the Ottoman rulers combined a devshirme system of recruitment for state institutions and a religious tax system based on Shariah law. Under the devshirme system “every year, a levy was made of male children from Christian families of the subject population in the Balkans: taken from their parents, they were sent to Constantinople or Anatolia to be reared as Muslims and trained for posts of command in the army or administration, as the immediate servitors of the Sultan” (Ibid: 366-367). The devshirmes provided some of top members of the state bureaucracy, “from the supreme office of Grand Vizir downwards through the ranks of provincial beylerbeys and sanjakbeys” and the entirety of the permanent army of the central state which was “composed both of the special cavalry of the capital, and the famous janissary regiments that formed the elite infantry and artillery arms of Ottoman power” (Ibid).

Under the Ottoman tax system, on the other hand, the non-Muslim populations would be burdened with additional taxes they would have to pay to the Sultan, the Ulemate (the religious institutions that trained cadres for the court system), and the Sipahis (the local tax collectors appointed by the Sultan who taxes timar regions of agricultural production) (Ibid: 371). Muslims were exempt from these additional taxes and the devshirme system. Hence there were economic incentives and coercive mechanisms for non-Muslims to convert to Islam, despite the absence of systemic mass conversions. Through this system, “both the ghazi tradition of religious conversion and military expansion, and the Old Islamic tradition of tolerance and tribute-collection from unbelievers, were conciliated” (Ibid).

Under the Ottoman systems of religious taxation and military recruitment, people of all religious beliefs were legally acknowledged as subjects of the sovereign. Sovereignty became the dominant ideological discourse as the dynasty evolved into the Empire. This shift was required to maintain the unity of the subjects of different ethnic and religious affiliations. At the same time, the whole territory of the empire was deemed the personal property of the Sultan, except for waqf religious endowments. The sovereignty of the Sultan was explicit in his right to exploit all sources of wealth within the borders of the Empire. There was no security of property other than that of the Sultan’s, which differentiated the Ottoman system from European feudalism. Hence the only mechanism for upward mobility was the state bureaucracy – the religious bureaucracy and the military bureaucracy. Justice, on the other hand, was served by different decentralized religious institutions based on the millet, or the ethnic or religious community, the subject belonged to. For the non-Muslim subjects, this implied a near absolute exclusion from the State apparatus (with the notable exception of military officers). The relationship between the non-Muslims and the sultanate shaped the structure of the new wave of racialized conflicts as the Empire went into crisis in the 18th and 19th centuries.

By the 18th Century, the timar and devshirme systems degenerated and the Empire was weakened by a series of defeats in the West and in the East and by economic stagnation (Ibid: 381-385). The infamous janissaries, which consisted largely of devshirme soldiers gained rights to remarry and own small shops in crafts. This led to their increased autonomy from, and eventual antagonism against the sovereign, as consecutive sultans tried to curb their growing political and economic power. The devshirme system and the Janissaries were eventually abolished, which effectively ended integration of new non-Muslim cadres to the state for a brief period. The timar system similarly deteriorated as, the sipahis could no longer compete with the European weaponry after industrialization (Ibid: 382). This lowered their ability to tax non-Muslims in the Balkans, which in turn further weakened their ability to subsist and pursue taxation. Another undercurrent was the economic stagnation and the new trade alliances. Britain, the first industrialized nation in the world, began to wield significant influence in the politics and the economy of the Ottoman Empire as “the Ottoman market… imported more English goods by 1850 than France, Italy, Austria or Russia, making it a vital region for Victorian economic imperialism” Ibid: 388).

This shift in trade was driven by a decline in agricultural productivity which also created the conditions for the transition from the timar system to the chiftlik system in the Balkans. The chiftlik system differed significantly from the timar system as the chiftlikholder “had practically unfettered control of the labour-force at his disposal: he could drive his peasants off the land, or prevent them leaving it by entangling them in debt obligations” (Ibid:386-387). Manorial reserves could be expanded at the expense of the tenants’ plots, which became a general pattern. The predominantly non-Muslim farmers in the Balkans were “left with a mere third of their output after payment of the land-tax and the fees for its collection” and “the condition of the Balkan peasantry sank together with that of the rest of Eastern Europe, towards a common misery” (Ibid) Farmers in the Balkans were now bound to the land and they could be legally recovered if they tried to leave. Holders of the chifliks on the other hand could be appointed by the sultan. This transformation was factor in the growing nationalisms in the region.

The degeneration of the old military and fiscal institutions, economic stagnation and the series of defeats against the European powers, led to serious restructuring of the Ottoman bureaucracy in favor of centralization of power in the hand of the sultan through the modernization of Ottoman institutions by ‘learning from the West’ (Ergin 2017: 48-67). The process of “fragmented modernization,” whereby state institutions were modernized selectively to centralize the sultan’s power, transformed the relationship of the Ottoman’s to the West, as Prussian, English or French infidels were now incorporated into and allowed to shape key institutions of the Empire.

The 19th century in the Ottoman Empire was defined by conflicts largely driven by nationalism, as the subjects of the empire, Christian and Muslim alike, struggled for national liberation against the sovereign in reaction to the new agrarian structure and with aid from colonial powers like the United Kingdom, France and Russia (Bethencourt 2013). It is in the 19th century we see the development of new racial discourses around Ottomanism, Islamism and Turkism. Up until modernization of the empire, the discourse of Islamism and sovereignty were the dominant justification of pre-capitalist colonization and exploitation of Muslims and non-Muslims alike. As the Ottoman Empire attempted to “westernize” under the conditions described above, the boundaries of the racial contract and the axes of the race-war were reshaped multiple times throughout the 19th century. Ergin describes the three main racial ideologies in the following;

Ottomanism would constitute the attempts to create a civic sense of belonging that would be inclusive of all ethnic and religious groups within the empire. The defining characteristic of the Ottoman identity would be citizenship and allegiance to the person of the sultan. Islamism, on the other hand, would emphasize the unity of Muslims within and outside the empire. An unending wave of nationalist uprisings by non-Muslim citizens of the empire in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries had produced an atmosphere ripe for claims of an Islamic nature. Finally, Turkism would entail redefining the characteristics of the Ottoman state around the Turkishness and extending this Turkish unity beyond the borders of the empire. (Ergin 2017: 68)

Ottomanism became the dominant discourse within the state bureaucracy throughout fragmented modernization until the end of the first constitutional period in 1878. Tanzimat period (1839-1878) promoted the rights of the non-Muslim citizens and allowed their independence from the Islamic institutions. Furthermore, the Noble Edict of the Rose Chamber (Hatt-I Şerif-i Gülhane) of November 3, 1839, introduced “the principles of individual liberty, freedom from oppression, and equality before the law” (Ibid: 61). The Imperial Edict of 1856 (Hatt-ı Hümayun) “addressed the issue of Christian citizens of the Ottoman Empire and continued the same concern about equality that emerged with the Noble Edict” (Ibid). December 1876 marked the high point for the Ottomanists, as the first constitutional period began, and a multi-ethic parliament was appointed. 42% of the members of the first parliament were non-Muslims (Ünlü 2014: 59) “In less than a year,” however, “Abdülhamid II indefinitely dissolved the parliament using his constitutional power. The Ottoman parliament would not reconvene again until 1908” (Ergin 2017: 61). Many of these structural reforms took place in order to maintain economic support of the British Empire and to maintain the non-Muslim subjects within the Empire as the non-Muslims were increasingly involved in secessionist nationalist movements.

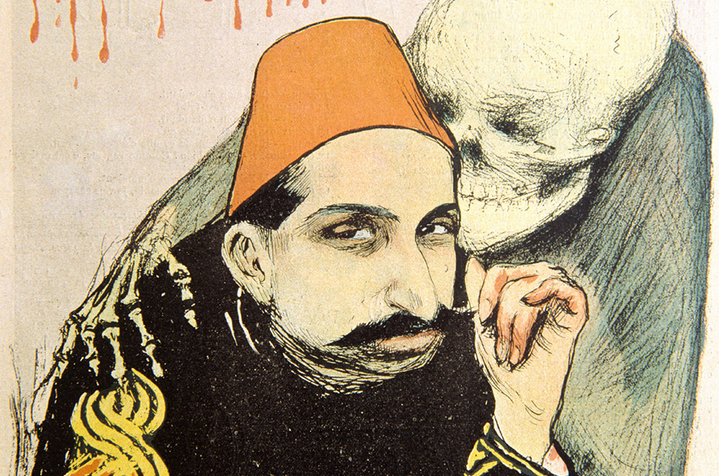

The dissolution of the first Ottoman parliament marked a shift on the state’s attitudes towards non-Muslims within the Empire. Islamism was revitalized under Abdülhamid II after the first constitutionalist period. The Muslim merchants, state bureaucrats and the sultan were concerned with the growing influence of the non-Muslims within the economy and the state. Tanzimat and the first constitutional era were failures as they neither satisfied the non-Muslim populations, nor did they satisfy the Muslims. The loss of the Ottoman-Russian war of 1878 and the large number of Muslim refugees that began to enter the Empire created an opportunity for Abdülhamid II to reframe the axes of the race war around Islam once again, as Ottomanism was no longer popular among large swaths of the population.

The new version of Islamism, however differed significantly from the earlier version as it lacked the tolerance element. Forced dispossession of non-Muslims became common practice (Karatasli and Kumral 2019: 535) which was fueled by the relative decline of the political and economic power of the Muslim merchants and the Sultan himself throughout the Tanzimat period. Muslims that were allied with non-Muslims, like the Alevis who were allied with Armenians, were not included in the new notion of Muslimness as their economic interests contradicted the mainly Sunni merchant class. Abdulhamid II founded the Asiret Mekteb-i Hiumayun, or Imperial School for Tribes in 1892, which trained Albanian, Arabic and Kurdish tribesman to assimilate them and their tribes into the new notion of Ottoman identity around Sunni Islam (Rogan 1996). The Kurdish and Armenian nationalists were both organizing for independence in eastern Anatolia at the time. Abdulhamid’s integration of the Kurds into the new notion of Ottoman nationalism around Islamism enabled him to take advantage of Kurdish tribes against the Armenians.

So far, we saw that throughout the pre-capitalist period in the Ottoman Empire, racialized discourses were not systematic, and they were reshaped multiple times for pragmatic reasons throughout the history of the Empire. In other words, the axes of the race war were transformed multiple times. In the earlier centuries of the Empire, an Islamism that included both conversionist and tolerant aspects of Islam was practiced by the Ottoman rulers. As the Empire began to lose influence among its non-Muslim subjects as it began to exploit them more aggressively, a universalism around multi-ethnic and multi-religious identity of Ottomanism was adopted. As this project failed due to various secessionist nationalisms and the dissatisfaction of the Muslim merchants and landowners, a reversion back to Islamism took place under Abdulhamid II, however, this new version of Islamism was much more militant and encouraged hostility towards the non-Muslim populations. The increased militancy of Ottoman Islamism during this period was in reaction to the growing nationalist movements among the non-Muslim subjects.

Republicanism and The Rise of the White Turk

Abdulhamid II’s Islamist policies failed to slowdown the decline of the sultanate power, as the territorial losses continued. New political movements were simmering within the newly reorganized state institutions. The most important one of these was without a doubt the Young Turks, who found the Committee of Union and Progress in 1889. The Young Turks were intellectuals and military officers who came out of “the military medical college and other modern educational institutions that Abdühamid II himself had supported” (Ergin 2017: 65). They were influenced by Comtian positivism and solidarism and were concerned with socially reengineering Ottoman society and state bureaucracy in order to modernize and ‘save the state’. The ideology of the Young Turks would heavily influence that of the Republicans who also believed in modernizing the state and the nation through social engineering.

Many of the Young Turks were refugees from the former Ottoman territories that were now occupied by Russian Empire. Hence, their identities were shaped more around Turkishness, alongside Islam, given that the areas Russian Empire occupied were literally called Turkistan and the ideologies of the race war in this context were informed by anti-Turkish discourses. The Turkism of the Young Turks was despite the fact that they knew very little about Anatolian Turks. The Russian invasion of Turkistan led to the formation of “a concrete intellectual link between Turkistan and the Ottoman Empire” (Ibid: 78). The Turkish intellectuals that would become the Young Turks “sought refuge in several European countries, but mostly in the Ottoman Empire, hoping to use these as bases to spread anti-Russian sentiments and a broad Turkic awakening” (Ibid). However, the Young Turks could not yet pursue explicitly Turkist policies, given that this would mean splitting up the state they obtained their power from. Hence initially the Young Turks were a lot more pragmatic in their ideological approach and aimed primarily to save the state.

Pogroms against non-Muslims had intensified since the 1890s, particularly those targeting the Greeks and Armenians who had the strongest nationalist movements (Karatasli and Kumral 2019: 535). The Young Turks initially promised a return to the Ottomanist universalism of the Tanzimat period when they first came to power by dethroning Abdulhamid II in 1908 (Ünlü 2014: 62). This resulted from pragmatic calculation as the state bureaucrats were largely tired of Abdulhamid II’s Islamist despotism, and also because the Young Turks were allied with the British Imperialists and Armenians (Keyder 1987). However, the pogroms organized by the local Muslim communities, particularly against Armenians destroyed the credibility of Ottomanism, and the losses of the Balkan Wars of 1912-13, which led to the loss of large sections of non-Muslim subjects through secessions, pushed the Young Turks to revert back to the Islamism.

Islamism of the Young Turks was also different from that of Abdulhamid II. Although, Abdulhamid II encouraged the dispossession of non-Muslims by Muslim Ottomans, his approach more pragmatic than systematic as his project was not a systematic restructuring. The Young Turks, on the other hand had a goal of establishing a national Muslim bourgeoisie through the dispossession of non-Muslims – particularly Greeks and Armenians (Karatasli and Kumral 2019: 537). For the Young Turks, the non-Muslims were an “an internal tumor” that needed to be purged for national salvation and saving the state (Akçam 2006). National salvation in this case required the construction of a national bourgeoisie through the positivist social engineering of the Young Turks.

Through the mass expropriation and exiles of Greeks and Armenians throughout the 1910s, the Young Turk government managed to transfer large swaths of land and other property into Muslim possession. These policies were decided by the central government, adopted, and enacted by local Muslim bureaucrats, merchants and landowners, and often involved the participation of the local peasants and workers as the tensions intensified (Ünlü 2014:64). As a result, “the non‐Muslim population in the Empire declined from 19.1% in 1914 to 2.5% in 1927” which “amounts to the disappearance of 90% of the pre‐war merchant, financial, and emergent non‐Muslim industrial bourgeoisie in Turkey” (Karatasli and Kumral 2019: 537).

However, the Young Turks failed to save the state or to form a national bourgeoisie, as large swaths of the Empire’s territories were either lost through secessions, or were occupied by the British, French and Italian imperial powers by the end of the first world war. Muslim small farmers and landlords, and former members of the Ottoman military bureaucracy began to organize their own nationalist movement around Muslimness, and eventually Turkishness. The Empire was now on its death bed and the Anatolian Muslims were occupied and “betrayed” by the non-Muslims. The localized institutions that fought against Greek and Armenian nationalists before and throughout the first World War, now allied themselves with the new independence movement led by commander Mustafa Kemal Atatürk.

The ideology of the independence movement led by Atatürk, was initially a continuation of the synthesis of Islamism and social engineering that was developed by the Young Turks. Until the War of Independence was won, the axes of the race war remained Muslims and non-Muslims, since the new movement did not yet attain state power. This orientation once again helped incorporate the Kurds, who had their own secessionist nationalism, into the Islamist independence movement. However, after the proclamation of the republic and through the constitution of 1924, the Turkism of the founders of the Republican came to the forefront as they struggled for a Turkish modernity through social engineering.

Early Republican period witnessed the development of systemic notions of racism, as scientific racism was blossoming all over the world at the time. The notion of improvement came to the forefront in reaction to the “backwardness” of the former empire. The goal was to “advance … to the level of the most prosperous and the most civilized countries of the world… to acquire the necessary resources and means for [the Republic] to live in nation-wide prosperity … to raise our national culture above the level of contemporary civilization” (Atatürk 1933). The struggle for modernity justified the overwhelming imposition of social engineering after the formation of the new state. The dispossession and deportations of non-Muslims continued until the 1940s, at which point most non-Muslim populations left the country or assimilated into Turkishness. However, the positivist Turkish modernity imposed by the Republicans also targeted its former Islamist and Kurdish allies, as these groups were now associated with the pre-modern character of the Ottoman Empire based on the official ideology. The Turkish modernity had to be secular and nationalist.

Many Kurds recognized reacted to this Turkification process early on (Ünlü 2014: 69),while others chose to assimilate to Turkishness as the state gave them new lands and businesses that were taken from the Armenians and Greeks. One of the most influential ideologues of the early Republican period, Ziya Gökalp, was a Kurd who adopted Turkishness as he came from a family of wealthy landowners (Karatasli and Kumral 2019: 540). On the other hand, those who refused to assimilate organized the first large scale uprising, the Sheikh Said rebellion, against the Republic in 1925 and were crushed as the state killed them by the thousands. The Sheikh Said Rebellion was uniformly described as a backward, pro-Sharia, feudal, pre-modern attempt to slowdown the process of Turkish modernization led by the managers of the Turkish State. The Kurdish rebellions continued as “of 18 major revolts that broke out between 1924 and 1938, 17 took place in the Kurdish regions” (Duzgun 2017: 432).

The intensifying opposition, primarily among the Kurds (both Sunni and Alevi) who made up the largest non-Turkish group within the country, required systematic attention by the Republicans for the “protection and improvement of the Turkish race.” Because of this, in the late 1920s and 1930s, the Republicans became increasingly invested in race science (Ergin 2017:99-133). Republican Peoples Party, the founding party of the Republic that controlled the single-party state, held multiple conferences where race, Turkishness and modernity were debated continuously and were systematically theorized. During this period, Turks were defined as an ancient race that rose from the steppes of central Asia and played a definitive part in nearly all world historic transformations from the fall of Rome to the end of the Dark Ages. Atatürk was the great modernizer who helped Turks climb back to their rightful place among the most civilized nations through crushing Ottoman backwardness and the imperialist infidels. It was argued that all world languages originally developed from proto-Turkish foundations. Language became one of the primary signifiers of Turkishness and the main axes through which the state aimed to assimilate all non-Turkish populations. Turks were also classified as white people from their origins. Chromatism, was another major curiosity of the early Republicans. Chromatic discourses persisted non-systematically and were eventually used against Kurds, Arabs, or African immigrants to challenge their Turkishness even if they were Turkish on the basis of citizenship.

The notion of citizenship is important as it divides Turkishness into two categories. The linguistic, culturalist, chromatist and historical discourses of Turkishness constitute the racial Turkishness. However, those who do not fully conform to these notions can still be Turkish on the basis of citizenship, as Turkey is defined exclusively as a modern state of Turkish people. This means that those who do not conform to the racial notion of Turkishness, but are Turkish on the basis of their citizenship must be saved from their pre-modern identity through assimilation.

Throughout the 1930s, the state banned the use of all languages other than Turkish and moved onto pursue a forced migration policy in order to assimilate the Kurds (Ibid, Cagaptay 2004). The existence of Kurdish language and people began to be denied during this period. Cultural practices were restricted. It was posed that the Kurds were simply confused about their Turkishness and could be improved through forced migration and education. Migration policies were planned to move the Kurds out of Turkish Kurdistan and resettle more Turks in the region. The modernized education system on the other hand functioned to reeducate all non-Turks to embrace their Turkishness by socializing them into the modern Turkish language, history, and customs. Not being a Turk simply represented Ottoman backwardness or treason. To be modern was to be Turkish.

So far, I did not explore the economic transformations Turkey underwent throughout the Republican period. Did Turkey become capitalist during the Republican restoration? The development of capitalism in Turkey took a unique path. Since the late Ottoman period, merchants in the region were involved in market relations with capitalist nations like Germany and Great Britain. However, the merchants were driven by market opportunities, rather than a market compulsion – which is what defines capitalist social property relations. The Republican period in many ways was a continuation of this relationship, as Turkish (non-Turkish peasants often faced forced expropriation by the state) small farmers largely maintained their landholdings until the neoliberal period, and the bourgeoisie largely avoided market competition given that the state itself had largely constructed the large agricultural and industrial bourgeoisie through selective redistribution of newly expropriated properties. It was no coincidence that “the first Turkish–Muslim businesses to emerge in the newly established Turkish Republic—such as Koç, Çukurova, and Sabancı (still amongst the largest Turkish companies today)—emerged in the aftermath of the deportations of non‐Muslims in the 1920s” (Karatasli and Kumral 2019: 538)

The bourgeoisie, in turn, continuously utilized the state to protect itself both from the lower classes and from international competition (Duzgun 2012). The bourgeoisie in most industries were oligopolists who controlled a large share of the private sector, while the state economic enterprises produced price controlled intermediate goods for the large bourgeoisie to shield them from international competition. It is difficult to argue that the Turkish bourgeoisie was reproducing itself under capitalist market compulsion. The conflicts between small farmers, the urban proletariat (which made up a small portion of the population until the 1980s), and the bourgeoisie, was largely mediated through the state rather than markets. When in the 1960s, the share of the urban populations increased for the first time due to the pull from state supported industrialization, and the first major workers movement came into life, the state became the employer of 36% of industrial workers and nearly one third of the workforce in order to siphon of the new mass of workers – many of whom still owned land.

Hence, Turkey did not fully become capitalist until much later given that the state continuously intervened in all market relations and protected property owners from market competition. The state led modernization efforts utilized an ideology of improvement for assimilation. Where the Young Turks failed, the Republicans succeeded in socially engineering a modern state and a national bourgeoisie. However, the ethnic homogeneity of this state was not attained as intended, as Kurds, Alevis and other oppressed groups continued their struggles for recognition and equality. At the same time, the ability of the non-Turk masses to assimilate to Turkishness shows that racial categories were not essentialized in the same way as they were in the case of former English colonies and the US. This might be because Turkey never fully transitioned to capitalism during the Republican period and until the 1990s. The state mediated rules of reproduction in Turkey enabled racialized groups to gain higher levels of recognition through being integrated into the state and assimilating to Turkishness on the basis of citizenship. Practices of forced migration, suppression of languages, Turkification through education continue to varying extents today, although the acknowledgments of other ethnic and religious groups are also more common (but still not legal). The higher levels of social recognition of oppressed groups today resulted from the decades long struggles that took place against state oppression.

Racism in Capitalist Turkey

So far, we have explored the race war and improvement discourses within the Turkish context. However, we did not find evidence of essentialization of race in the same manner as in the case of the English colonies. Was race essentialized in Turkey after the society became increasingly market dependent? Can non-Turks assimilate to Turkishness today? The argument for this will be briefly explored in this section.

According to Duzgun, Turkey fully transitioned to capitalism because of a series of reforms throughout the 1990s and 2000s which came in the face of the recurrent social and economic crises. These reforms liquated the small farmers as they were now compelled to compete with international producers without state protection, privatized a large section of state economic enterprises, and exposed the national bourgeoisie to intense international competition. Hence, we need to look at how race functions in contemporary Turkey to understand how race and capitalism work in the Turkish case.

The argument I make is based on the experience of the Syrian refugees in Turkey. Nearly all other marginalized groups within Turkey have been represented within the Turkish parliament and state bureaucracy by the 21st century by only assimilating into Turkishness on the basis of citizenship, although of course economic and political inequalities continue as citizens and politicians who do not fully assimilate are continuously prosecuted by the state. While the rest of the groups are considered Turks, on the basis of their citizenship status (Ergin 2017), Syrian refugees represent a unique case whereby their lack to legal-political equality is justified based on their non-Turkishness. There are currently more than 3.5 million Syrian refugees in Turkey (Özdemir 2020). Syrian refugees initially only had a right to education and healthcare based on their temporary protected status, and they gained the right to work permits in 2016 (Vammen and Lucht 2017). However, as of 2019, less than thirty thousand refugees had a legal work permits while more than two million refugees are working age (Akdeniz 2019). Only 26 million people in Turkey are officially employed, which means that the number of Syrian refugees nearly equal 10% of the employed labor force.

The high number of Syrian refugees forms the backbone of the informal economy and creates downward pressure on wages. Turkey hasn’t had an unemployment rate lower than 8% in the last 15 years (OECD 2019) and the influx of high number of refugees intensified competition for jobs as the country went into recession in late 2018. Refugee children are more likely to be employed in the informal economy or forced into beggardom as they are more likely to starve due to the shortage of state economic support and the legal exclusion of their parents from the labor market.

Syrian refugees began to enter Turkey in 2011 after the start of the Syrian civil war and they have lacked the legal right to work for nearly a decade. All parties of the state, with the exception of some members of the pro-Kurdish HDP, are unwilling to give equal rights to Syrian workers as they help lower the wages for capitalists through their willingness to work informal jobs for less than minimum wage with no benefits. In the 2019 local elections the main opposition parties, the Republican People’s Party (which officially described itself as social democratic since the late 1960s as it was pressured by the labor movement but continues its support for ethno-nationalist policies) and the İYİ Party (a Turkish nationalist party that poses as center-right) openly ran on mass deportations of Syrian refugees on the basis that the state was wasting too much of its resources on people who aren’t Turkish (Yeniçağ Gazetesi 2018, 2019). Both parties were relatively successful given that the pro-kurdish social democratic HDP also backed them in all major cities as part of a popular front strategy. Hence only alternative to the AKP, who was largely responsible for the recession and high levels of poverty and unemployment, was the ethno-nationalist opposition. AKP almost immediately began deportations of refugees who did not have official refugee status once it was defeated in the local elections, however it refused to pursue any other policies regarding the refugees since then. AKP’s shift encouraged more hostility against Syrian refugees in the form of pogroms and murders.

The unique case of Syrian refugees appears to parallel more closely with the racial discourses of capitalism. Syrian refugees cannot become Turkish due to their essential differences which justifies their exclusion from legal-political equality. Although the racial discourses against Syrians were similar to those of the early Republican period, they were essentialized. Syrians were chromatically, linguistically, and culturally different from the Turks. They were not as modern as the Turkish nation due to their Arabness. Hence their integration to Turkishness was simply not possible. While the rest of oppressed groups are still racialized through the discourses of modernization based on the different places they occupy within the political economy, their Turkishness based on citizenship status enables them access to legal-political equality, at least on a symbolic level. The case of the Syrian refugees shows on the other hand that Turkey’s transition to capitalism created the conditions for modern racism whereby the legal-political inequality of non-Turks are justified through their essential differences from the Turks.

Before I conclude, it is important to note that racialization groups who are only Turkish on the bases of citizenship continues today. The policies of mass expropriation of the Kurds for example led them to move into the western parts of Turkey (Karatasli and Kumral 2019: 548). Approximately 1.5 million Kurds left their homes throughout the 1990s as the armed conflicts between the secessionist Partiya Karkeren Kurdistan (PKK) and the state intensified. In western cities, Kurds became the most exploited members of the urban proletariat as they were often excluded from high paying jobs due to racial discrimination. The oppression of Kurds was often justified based on their chromatic differences from Turkish whiteness, and the way they spoke Turkish. Given that the state was highly influential in the creation of the bourgeoisie and the division of labor, and that Kurds were only Turks on the basis of citizenship, Kurds were systematically pushed into the sections of the economy where they worked for lower wages, less benefits and more intense working conditions.

Hence, we have seen that the Turkish transition to capitalism since the 1990s created the conditions for racism based on essential differences. Assimilation is still possible for those who are Turkish on the basis of citizenship, however if they do not conform to the chromatic, linguistic and cultural practices of modern Turkishness as defined by the hegemonic discourses, they could be discriminated against. On the other hand, the Syrian refugees who are not Turkish in any way, are prevented from equal rights and access to jobs on the basis of their essentialized non-Turkishness, as they continue to be pushed into the informal economy where they are hyper exploited. The non-Turkishness of Syrians are also justified by essentialized chromatic, linguistic, and cultural differences.

Conclusion

Racism is justified through three unique discourses through the transition from pre-capitalist forms to capitalist social property relations. Ideologies of race-war are arbitrarily utilized for the purposes of political and economic domination of racialized groups under pre-capitalist forms of accumulation. The discourse of improvement establishes systematic thesis of racial superiority; however, assimilation is still possible through the process of improvement. Once capitalist social property relations become the dominant socio-economic relations, race becomes essentialized based on the historical discourses. The essentialized characteristics are used to justify legal-political inequalities as well as economic inequalities the racialized groups experience. In the case of Turkey, we have seen that chromatic, culturalist and linguistic essentialisms of Turkishness emerge throughout the Republican attempts to socially engineer modernity. The state becomes strong enough to intervene in all aspects of social life which slows down the establishment of capitalist social property relations. The modernization process still allows the possibility for those who are not racially Turkish to assimilate into Turkishness. Once, capitalist social property relations become dominant, racialized Turkishness becomes essentialized. This is evident in the racist discourses used against Syrian refugees and the Kurds.

Bibliography

Akçam, Taner. 2006. “The Ottoman Documents and the Genocidal Policies of the Committee for Union and Progress (İttihat ve Terakki) toward the Armenians in 1915.” Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal 1(2).

Akdeniz, Ercüment. 2019. “CHP Bilim Platformu, mülteci notları yayımladı.” Evrensel.net. Retrieved May 26, 2020 (https://www.evrensel.net/haber/376487/chp-bilim-platformu-multeci-notlari-yayimladi?a=be09d).

Anderson, Perry. 2013. Lineages of the Absolutist State. Verso.

Arango, Tim. 2015. “A Century After Armenian Genocide, Turkey’s Denial Only Deepens.” The New York Times, April 16.

Ataturk, Mustafa Kemal. 1933. “Nutuk (Grand Discourse of Ataturk).” Retrieved May 25, 2020 (https://www.aydin.edu.tr/en-us/arastirma/arastirmamerkezleri/atam/Pages/10.-Y%C4%B1l-Nutku.aspx).

Balibar, Etienne. 2002. “‘Possessive Individualism’Reversed: From Locke to Derrida.” Constellations 9(3):299–317.

Bethencourt, Francisco. 2013. “The Impact of Nationalism.” Pp. 309–34 in Racisms, From the Crusades to the Twentieth Century. Princeton University Press.

Bhandar, Brenna. 2018. Colonial Lives of Property : Law, Land, and Racial Regimes of Ownership. Durham : Duke University Press.

Birgun Gazetesi. 2020. “Metropoll anketi: Erdoğan’ın görev onayı yüzde 41,9’a düştü.” birgun.net. Retrieved May 20, 2020 (https://www.birgun.net/haber/metropoll-anketi-erdogan-in-gorev-onayi-yuzde-41-9-a-dustu-286577).

Botwinick, Howard. 2018. Persistent Inequalities: Wage Disparity under Capitalist Competition. Brill.

Brenner, Johanna, and Robert Brenner. 2016. “Reagan, the Right and the Working Class.” Versobooks.Com. Retrieved May 22, 2020 (https://www.versobooks.com/blogs/2939-reagan-the-right-and-the-working-class).

Brenner, Robert. 1985. “The Agrarian Roots of European Capitalism.” Pp. 213–328 in The Brenner Debate: Agrarian Class Structure and Economic Development in Pre-industrial Europe, Past and Present Publications, edited by C. H. E. Philpin and T. H. Aston. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cagaptay, Soner. 2004. “Race, Assimilation and Kemalism: Turkish Nationalism and the Minorities in the 1930s.” Middle Eastern Studies 40(3):86–101.

Duzgun, Eren. 2012. “Class, State and Property: Modernity and Capitalism in Turkey.” European Journal of Sociology 53(2):119–48.

Duzgun, Eren. 2017. “Agrarian Change, Industrialization and Geopolitics: Beyond the Turkish Sonderweg.” European Journal of Sociology 58(3):405–39.

Ergin, Murat. 2017. “Is the Turk a White Man?”: Race and Modernity in the Making of Turkish Identity. Brill.

Fields, Barbara. 1990. “Slavery, Race and Ideology in the United States of America.” New Left Review 181:95–118.

Foucault, M., Mauro Bertani, A. I. Davidson, A. Fontana, F. Ewald, D. Macey, and Collège de France. 2003. “Society Must Be Defended”: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1975-1976. Allen Lane.

Karatasli, Sahan Savas, and Sefika Kumral. 2019. “Capitalist Development in Hostile Conjunctures: War, Dispossession, and Class Formation in Turkey.” Journal of Agrarian Change 19(3):528–49.

Keyder, Ç. 1987. State and Class in Turkey: A Study in Capitalist Development. Verso.

Locke, John. 1960. Two Treatises of Government. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

OECD. 2019. “Unemployment – Unemployment Rate – OECD Data.” TheOECD. Retrieved May 26, 2020 (http://data.oecd.org/unemp/unemployment-rate.htm).

Özdemir, Ahmet Selman. 2020. “Türkiyedeki Suriyeli Sayısı Nisan 2020 – Mülteciler Derneği.” Retrieved May 26, 2020 (https://multeciler.org.tr/turkiyedeki-suriyeli-sayisi/).

Post, Charlie. 2017. “Comments on Roediger’s Class, Race and Marxism.” Salvage. Retrieved May 21, 2020 (https://salvage.zone/online-exclusive/comments-on-roedigers-class-race-and-marxism/).

Roediger, D. 2017. Class, Race, and Marxism. Verso Books.

Roediger, D. R., and E. D. Esch. 2014. The Production of Difference: Race and the Management of Labor in U.S. History. Oxford University Press.

Rogan, Eugene L. 1996. “Asiret Mektebi: Abdulhamid II’s School for Tribes (1892-1907).” International Journal of Middle East Studies 28(1):83–107.

Tuckness, Alex. 2020. “Locke’s Political Philosophy.” in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by E. N. Zalta. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University.

Ünlü, Barış. 2014. “Türklük Sözleşmesi’nin İmzalanışı (1915-1925).” Mülkiye Dergisi 38(3):47–82.

Vammen, Ida Marie, and Hans Lucht. 2017. REFUGEES IN TURKEY STRUGGLE AS BORDER WALLS GROW HIGHER. Danish Institute for International Studies.

Yeniçağ Gazetesi. 2018. “Meral Akşener: ‘Suriyelileri geri göndereceğiz.’” Yeni Çağ Gazetesi. Retrieved May 26, 2020 (https://www.yenicaggazetesi.com.tr/meral-aksener-suriyelileri-geri-gonderecegiz-213619h.htm).

Yeniçağ Gazetesi. 2019. “Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu: ‘Suriyeliler evine dönmeli.’” Yeni Çağ Gazetesi. Retrieved May 26, 2020 (https://www.yenicaggazetesi.com.tr/kemal-kilicdaroglu-suriyeliler-evine-donmeli-225402h.htm).

Žmolek, Michael Andrew. 2013. Rethinking the Industrial Revolution: Five Centuries of Transition from Agrarian to Industrial Capitalism in England. Brill.