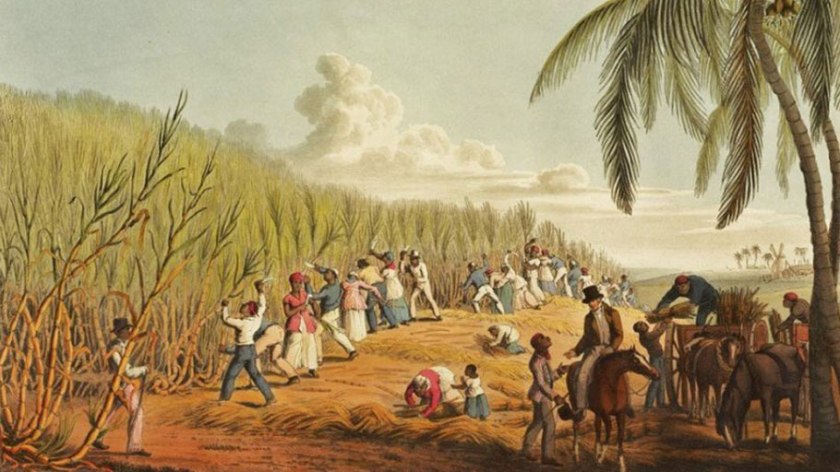

Slavery has played a defining role in the development of the ‘New World’, the United States and contemporary capitalism. Today, as the US faces a “racial reckoning,” interest in the history of slavery has spiked. Whether it be the 1619 Project published by the New York Times Magazine (2019) that aims to historicize racial slavery, or Deep Roots (Acharya, Blackwell, and Sen 2020),which aims to look at the ongoing impact of slavery in shaping contemporary political opinion, or a series of books that frame slavery in the context of “the new history of capitalism” (NHC) (Baptist 2016; Beckert 2014; Johnson 2013), the historical study of slavery is today perhaps more popular than it has ever been in recent history. One commonality of the recent literature on slavery has been the overwhelming emphasis on the role of race while often de-emphasizing the relationship between capitalism and slavery.

The contemporary literature also rarely takes a comparative approach to slavery, hence avoiding both the historical and the international context of British colonial and American plantation slavery. Historical study of slavery must go beyond simply framing the issue as America’s original sin. An earlier work, Slavery and Social Death by Orlando Patterson (1982), develops a grand theory of slavery from Rome all the way to the antebellum South. Patterson’s grand historical approach, while rich in historical examples, misses the specificity of the social dynamics of slavery under capitalist market compulsion. This has been the flip side of the coin, as grand theories often tend to miss the historical particularities of different social dynamics.

To make up for the shortcomings of the previous literature, two key dynamics must be analyzed comparatively: (1) the relationship between race and slavery, and (2) the relationship between capitalism and slavery. While racialization has often played a part in enslavement, I will argue that the co-constitution of an exclusively racial system of plantation economy under capitalist market compulsion has only taken place in the plantations of British colonies in North America. For the purposes of this paper, I will try to sketch out a theoretical approach for understanding the economic role of slavery, building on a critique of Patterson in order to elaborate the historical relationship between race, slavery, and capitalism.

Capitalism, Race and Slavery

Capitalism as Market Dependence

For clarity we must begin the analysis through defining our key terms: capitalism, race, and slavery. How one defines each of these terms has major theoretical implications. My definition of each of these terms is informed by a single principle: historicity. Ellen Wood (Foreword to Post 2011) once said: “There are essentially two ways of thinking about history unhistorically. One is to posit a single, universal transhistorical law of change and development. The other is to reduce history to a welter of particularities, all detail and difference without causality or even process, just, in Arnold Toynbee’s classic phrase, one damn thing after another.”

Historians have often argued that capitalism[*], race[†], or slavery[‡] are transhistorical relationships that have lives of their own and appear in different forms throughout human history. This view however does not satisfy historicity, since if one imposes a transhistorical nature on a social phenomenon, the phenomenon appears to be simply a natural part of social life. Hence one no longer needs to explain the origins, or the possible end of the given phenomenon. Capitalism, race, and slavery have historical beginnings and have been exclusively reproduced under a certain set of social conditions. A historical definition of these concepts then must be based on the set of social relationships that allow for their reproduction on an ongoing basis.

In constructing a historical definition of capitalism, the most progress has been made by the so called Political Marxists (Brenner 1976, 1985; Lafrance and Post 2018; Wood 2002)[§]. For Political Marxists, capitalism is defined as market dependence as the regulating socio-economic relationship among direct producers as well as the owners of the means of production. This means that both direct producers and the owners of the means of production must compete in the market in order to reproduce their material existence. For the direct producers, this means competing for a limited number of jobs, while for the owners of the means of production it means maximizing their surplus in order to accumulate a larger quantity of capital[**] to run their competitors out of business. Political Marxists counterpose market dependence to markets as opportunities, as in the former one is structurally compelled to sell while in the latter one can sell when the economic opportunities arise for profitable transaction.

The preconditions for market dependence are (1) separation of the direct producers from the means of production and (2) the dominance of market mechanisms for exploitation (accumulation of economic surplus). The establishment of these preconditions is historically contingent and develop in various ways based on the specific dynamics of class struggle in a given context. For our purposes we will explore how market dependence has shaped slavery in the British colonies in North America, while its absence has led to different economic relations in former Dutch, Spanish, and Portuguese colonies.

Race as Ideology

Moving towards defining race, we can start with the observation that in societies where in-group-out-group dynamics are utilized for designating social status, an ideology of social differentiation would emerge naturally to justify differentiation. The ideologies of differentiation might be expressed through some discourses that aim to essentialize social status of lower ranked groups. Foucault argued that racism is an expression of permanent social war between competing social groups (Foucault et al. 2003). However, so long as the society allows for the upward mobility of lower-ranked subjects, the discourses of social differentiation will not be self-reproducing, since once lower-ranked subjects move up, the discourse no longer describes a real social condition. As Barbara Fields (1990: 112) puts it “An ideology must be constantly created and verified in social life; if it is not, it dies, even though it may seem to be safely embodied in a form that can be handed down.”

What would make such an ideology “racism” is when the social status becomes unchangeable within the given social context. In this regard Foucault also highlighted the fact that the widespread popularity of biological racism parallels the rationalization of the capitalist state, which integrated racial categories into its own mechanisms of reproduction through the law (Ibid). From these observations we can define race as an ideology of social differentiation that self-reproduces in contexts where the conditions of differentiation cannot be overcome. For our purposes we will primarily explore the development of racialized slavery and how its development in various colonial contexts have led to various racial ideologies. The role of the state is the crucial factor in allowing for the reproduction of racial ideologies through coding it into law.

Pre-Modern Slavery and Slavery as Property

Defining slavery poses its own challenge. In this regard it might be helpful to work through Patterson’s (1982) definition and explore its strengths and shortcomings. For Patterson, slavery is defined by one’s captivity under direct coercion, their “social death”, and their essentialized social position as dishonored and degraded through political mechanisms of authority. As in Hegel, in Patterson’s work slaves are socially dead, dishonored, and captive people, can only be defined by their relationship to their master. However, this is an uneven codependence, where the master himself is dependent on the slave to realize his own social power. The power of the master is simultaneously reinforced through the legal status of the slave as a non-person.

The main problem with Patterson’s work is that his understanding of slavery often undermines the role of slavery as an economic relationship. This appears to be largely informed by Patterson’s inclination to construct a grand theory through exploring the phenomenon of slavery across world history. This results in a focus on the socio-political dynamics over economic ones, given slaves in pre-modern societies were not primarily used for economic exploitation.

Patterson’s approach is most problematic when he discusses the relationship between slavery and the notion of property. For Patterson, slavery is not defined by slaves being property, but by being incapable of becoming owners of property. He argues this point through drawing parallels between slavery and the exchange of athlete contracts, dowry, “human capital investments” and also that of exchange of labor power in general in pre-modern societies which supposedly suggest that ownership of services can be sold whether or not one is enslaved. What is unique in the case of slaves, then, is their inability to acquire property due to their legal non-personhood.

The condition of the slave as property is unique, not in general, but in societies where private property rights are enforced by state mechanisms and exist under a capitalist imperative of competition. Masters in these types of societies, such as the antebellum US South, outsource some of the coercion required to reproduce the institution of slavery. Hence the power relationship is defined by slave’s economic situation as property by the state. The property relationship under plantation slavery maintained an economic incentive not to physically harm slaves, given that slaves were the main form of ‘machinery’ that produced the profits of the masters. This is in part why slave patrols were created, in order to ensure the safety of the masters’ ‘property.’ Robin Blackburn (1998: 10) describes this difference in the following:

Roman slaves were sold because they had been captured, while many African slaves entering the Atlantic trade had been captured so that they might be sold. Likewise, the estates of the Roman Empire generally marketed less of their output and relied less on purchasing inputs than was the case for the plantations of the Americas. Consequently, accounting methods and financial instruments were less elaborate. The slaves of Rome also had a much better chance of ending up in some non-menial job. Roman slavery was highly geared to the capacities of the imperial state, … in the New World the colonial states strove to batten upon a ‘civil slavery’ geared to commercial networks spread across and beyond the Atlantic – and eventually this civil slavery was emancipated from metropolitan tutelage.

Patterson does acknowledge the slaves’ capacity to move up the ranks in pre-modern societies. The chapter called the Ultimate Slave highlights slaves who were able to gain social statuses that were relatively privileged in comparison to certain non-slave populations. Roman slavery, Ottoman slavery and some others provide great examples of this. However, the inability of slaves to attain such positions within the British colonial plantations highlights this most significant difference between the British colonial slavery and pre-modern slavery. The main consequence of this lack of social mobility under a formally egalitarian political system is that it necessitated the essentialist racial ideologies of British colonial, and later American, slavery in order to justify the slaves’ social condition (Charlie Post 2017).

The point of this section was to clarify the historical specificity of plantation slavery in the British colonies in North America in relation to three notions: (1) The presence of capitalist market compulsion has impacted the dynamics of plantation slavery in the British North American colonies while it did not directly influence those in the other colonies (2) Racial ideologies became necessary to explain the permanent unfree condition of massive slave populations in a formally free and egalitarian society, and (3) These two dynamics led to a particular form of racial slavery under capitalist market compulsion that is exceptional in comparison to other historical forms of slavery where slaves are often eventually allowed manumission or formal freedom. In the next section I will provide historical evidence to build on the line of argument developed above.

Colonial Slavery: Absolutist and Capitalist

The Absolutist State and Capitalism

In order to explain the historical variations in the types of colonial slavery we must first explain the variations among the types of states that were engaged in the New World slave economy. In this regard we can observe two different types of European states who developed different types of slave systems in the New World: the absolutist states and the bourgeois state.

The development of the absolutist state in Europe was a consequence of the crisis of feudalism in Europe in the 14th century. The decline in agricultural yields due to increased subdivision of land has intensified class conflict (Brenner 1985). The intensification of class conflict yielded different results in different geographic regions. In areas where peasants were organized effectively, they were able to fix their taxes, whereas in areas with weak peasant organization, the lords were able to exert more power and impose harsher control over the peasants.

According to Brenner only in the English countryside did the intensification of conflict lead to the proletarianization of poor peasants through dispossession, and the competitive leasing of land to rich peasants created the structure of agrarian capitalism through making both market dependent. Nonetheless, the intensification of class conflict led to the centralization of power and movement of authority upwards across Europe and formation of absolutist states. According to Anderson (2013: 18),

Absolutism was essentially just … a redeployed and recharged apparatus of feudal domination, designed to clamp the peasant masses back into their traditional social position – despite and against the gains they had won by the widespread commutation of dues … the Absolutist State was never an arbiter between the aristocracy and the bourgeoisie, still less an instrument of the nascent bourgeoisie against the aristocracy: it was the new political carapace of a threatened nobility.

While agrarian capitalist relations existed in the English countryside, this did not immediately lead to their domination or the transformation of the state into a capitalist one. However, by the time British colonial slavery was taking off the British state, unlike other absolutist states, had already gone through the transformation in becoming a bourgeois state that was market dependent. While this meant that the English agrarian capitalists, merchants, early industrialists, planters, and proletarians were all functioning under market dependent conditions of social reproduction, the rest of the European economies were still primarily structured around collecting agricultural surpluses through non-economic and coercive mechanisms of exploitation.

The internal market competition within the British home market and the colonies allowed for more rapid development of the productive forces while the absolutist states had to play catch up through investing their agricultural surpluses in infant industries, mercantile trade, and colonial wars. The absolutist states formed state sanctioned merchant monopolies in order to expand their colonial efforts. As Post (2017) puts it:

State-sanctioned merchant companies were often behind the trade and colonization efforts; thanks to the governments that supported them, they tended to enjoy monopolies in the provision of slaves and other imports (tools, food, clothing) as well as in the marketing of colonial produce (sugar, coffee, cotton)… French planters, unlike British and later US planters who were legally subject to … seizures [of their property] when they did not pay their debts, avoided market dependence and the associated subjection to market compulsion. As a result, absolutist colonization reproduced feudal dynamics outside of Europe.

The monopolist merchants that were backed by their absolutist states did not function under market dependence. In contrast the English ‘new merchants’ were “derived from ranks of shopkeepers and sea captains” who “competed among themselves to supply American colonists with laborers (initially indentured servants, later slaves), food, clothing, and tools as well as to supply English consumers with the planters’ tobacco, sugar, and coffee. (Ibid)” because the property of English merchants could be seized by the state if they did not pay their debts. Hence British planters, merchants, and industrial capitalists were compelled by market competition to invest their profits in order to reproduce their class positions. This difference between the monopolist merchants and the ‘new merchants’ who were capitalists shaped the differences in the formation of plantation slavery across different colonies.

Origins of the Slave Trade

In the pre-modern era, slaves were sold because they were already captured while during the modern period slaves were captured to be sold (Blackburn 1998). It is important to explain why commercial slavery became one of the primary sources of labor throughout the European colonization of the New World.

The origins of the transatlantic slave trade lie in the European exploration of the New World. Following the crisis of feudalism, alongside the absolutist states came the age of discovery. The exploration of the New World by Europeans was driven by the fiscal needs of the absolutist states of Europe. As European ‘explorers’ found vast resources in the New World, mainly gold in the earlier Portuguese expeditions, they needed a larger labor force to be able to extract more of what they found (Ibid : 110). Before 1453, Europeans got slaves from Eastern European “Slavic” populations. But the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople cut off access to those populations, forcing Europeans to look elsewhere for slaves. A sizeable slave trade had already existed between Western Coast of Africa and the east Mediterranean prior to the European expeditions to the New World. Hence initially the Portuguese, then the Spanish, the Dutch, and the others utilized the West African slave markets for a cheap labor force to utilize during their expeditions, and eventually for the settlements. As the scale of colonial plunder increased so did the ability of the colonists to purchase more African slaves from West African slave merchants who demanded sugar, arms, and other European exports.

Slave economies controlled by mercantilist monopolists were forced to be more lenient on manumission. There were two main reasons for this. First, the African slaves vastly outnumbered the colonial merchants and planters in the West Indies and Brazil from an earlier point. This forced the merchants and planters to allow for a higher population of free blacks to prevent revolts. Second, because they were not under market compulsion to maximize profits, they did not have systematic imperative to maximize the profits they could squeeze out of slaves. This might have made them more indifferent to the freedom of larger numbers of slaves in comparison to their counterparts.

Colonies in the British North America on the other hand functioned under market dependence and primarily relied on European indentured servants as a labor force until the second half of the 17th century. When these colonies began to import black slaves on a mass scale, permanent slave status had already been racialized. Market dependence in the absence of wage-laborers that could be laid off prevented planters from investing in new technologies, as this would devalue the capital they owned in the form of slaves (Lafrance and Post 2018:165-191). Hence planters primarily chose to invest their capital in more land and more slaves as this was the only way they could maintain the value of the capital they owned while also increasing their profits. The increased investments in black slaves led to a significant increase in their population as they became a near majority in the prerevolutionary South.

Colonial Slavery and Race

Under feudal-absolutist state formations, class inequality is engrained to the law which historically had religious character. Hence in these societies there has been no external ideological justification required for forms of slavery beyond this. Blackburn (1998: 12) describes the racial ideologies of colonial states in the following

The early Spanish and Portuguese authorities justified slavery as a means to the conversion of Africans. European traders and colonists of the early modern period had few qualms about the enslavement of heathens, whether Native Americans or Africans or – if they could get away with it – Asians, while they rarely displayed any eagerness to convert them. But some slaves converted nonetheless, putting a strain on both official and popular conceptions. In the English colonies specific legislation was to be enacted by the local assemblies stipulating that conversion did not confer freedom on the slave.

For the absolutist states it was adequate to identify slaves as heathens to justify their position. Christianity and Islam were both tolerant of slavery during the early modern period. Most importantly, the colonial territories under absolutist control also allowed some slaves manumission on conversion. Conversion to Catholicism was how the Portuguese initially justified the enslavement of West Africans. Manumission, religious or otherwise, was a mechanism to make the management of vast numbers of African slaves easier, particularly in Dutch, French, Spanish, and Portuguese colonies, as black populations outnumbered those of whites in each of these slave colonies by the 17th century.

The relatively widespread manumission of slaves in the absolutist colonies created a significant population of free blacks. By the end of the colonial period the eight largest jurisdictions in Brazil (which was the largest slave colony in the West) had whites to have “comprised 28 per cent of the population, closely followed by free blacks and mulattoes (27.2 per cent), slaves (38.1 per cent) and Indians (5.7 per cent). Even in the provinces where slaves were most numerous, they did not constitute the majority of the population – 46 per cent of Maranhao’s population, 47 per cent of Bahia’s and 45.9 per cent of the population of Rio de Janeiro” (Ibid: 492).

In the West Indies, which had come under British control during the middle of the 17th century, by the 1800s only about half of the black population worked in the sugar plantations (Wesley 1932: 54). The rest were “comprised of artisans, herders, domestics, watchmen, nurses, the aged and the children (Ibid).” Free blacks in the West Indies often accumulated significant wealth of their own. According to Wesley:

In Grenada, the free colored population was more than three times as numerous as the white population, and they were described by a resolution of the Assembly as “a respectable, well-behaved class of the community and possessed a considerable property.” The free blacks and free persons of color in Kingston, Jamaica, were referred to as persons of great wealth. It was said that seventy persons among them had aggregate wealth of “about one million of property and the heads of all families may be considered as possessing some little freehold or other.”

British colonies in North America followed similar logic until the middle of the 17th century. Until the 1660s, black slaves in the North American colonies could often gain their freedom. At this time, the difference between the conditions of African slaves and European indentured servants were marginal as the two groups worked, lived, and often formed families together. Blackburn (1998: 240) notes that in Virginia, ‘Antonio the Negro’, sold as a slave in 1621, survived to become the freeman Anthony Johnson in 1650, married to an African woman and owning cattle and 250 acres.”

Colonial Virginia, which eventually became the largest colony in North America set the precedent for the unique racial institution of slavery in North American colonies(Lafrance and Post 2018: 165-191). Virginia was a major tobacco exporter since the 1620s. Planters in Virginia primarily relied on European, and some African indentured servants as a labor force for tobacco production. However, as the tobacco prices began to decline in the 1660s, the planters attempted to reduce labor costs by extending length of indenture and impose strict punishments for runaway servants. A peace agreement with native Americans closed the westward expansion of the colony, which meant that the land indentured servants could settle in became increasingly limited. The increased intensification of labor, length of tenures and the dearth of land for future settlement led to a decline in the inflow of new indentured servants and to Bacon’s Rebellion in 1676, the largest rebellion in North America prior to the revolution.

Planters had begun to realize that indentured servants could no longer provide a suitable labor force for tobacco production. They had begun to transition from a labor force predominantly made up of indentured servants to one that was predominantly made up of slaves. In 1661, “the Virginian Assembly extended statutory recognition to slavery, both African and Indian, and in the following year it ruled that all children born to slave mothers would themselves be slaves” (Ibid: 250). Following this up in 1667, the Virginian Assembly banned manumission by declaring that “‘the conferring of baptism does not alter the condition of the person as to his bondage or freedom (Ibid:251)” Parallel attempts were taking place in Barbados and certain parts of the West Indies, however; since blacks made up the majority of the population in the West Indies, the attempts for permanent enslavement of blacks were not equally successful.[††]

The legal recognition of racialized slavery in Virginia led to an increase in the population of black slaves as they were cheaper than indentured servants. Morgan (2003) estimates that the number of black tithables in Virginia colony were approximately 1,000 (about 1% of the population) and this number increased by ten times before the end of the century. By the 1690s, black slaves approximated about 25 to 40 percent of the population while making up almost the entirety of the plantation labor force.

Other states like Maryland and South Carolina imposed similar laws during the same period. In Maryland the percentage of the population that was enslaved doubled between 1704 and 1750 (Ibid, Historical Statistics of United States 1970). By the middle of the 18th century, slaves made up 30% of the population in Maryland, 43% of the population in Virginia and 60% of the population in South Carolina.

Racial Ideologies, Slavery and Capitalism

The white yeomanry (small farmers and artisans) in the British North American colonies stood between the planters and the slaves, while in Brazil in the West Indies this intermediate position was occupied by free blacks. This effectively prevented manumission in the British North American colonies and the American South as the planters were economically compelled not to free slaves, while the white yeomanry was legally compelled not to fraternize with black slaves.

Within the span of a century racial ideologies justifying the inherent inferiority of black slaves developed across the US, despite the fact that ancestors of the white yeoman had often worked alongside black servants. Fields (1990: 101) states,

Strong belief in the value of social independence led the non-slaveholders to share with planters a contempt for both the hireling labourers of the North and the chattel slaves of the South; it also bred in them an egalitarian instinct that never gracefully accepted any white man’s aristocratic right to rule other white men—a right the planters never doubted with regard to the lower classes of whatever colour.

The market dependent development of plantation slavery under racial legal system provided the demographic dynamics that allowed for fertile terrain for ongoing reproduction of racial ideologies. The persistence of legal and economic inequality between the white yeomanry and black slaves in the British North American colonies, and later the American South, persisted until the abolition of slavery. Hence, so did the structural basis for racial ideologies.

After the abolition of slavery, for the first time since Bacon’s rebellion, Black sharecroppers occupied the same class position as white yeomanry as by “the late 1870s and early 1880s, a substantial portion of independent-white farmers had lost title to their lands and were reduced to cash-tenants or sharecroppers of the merchant-landlords of the upcountry-South. (Post 2011: 265)” This created the basis for the southern Farmers’ Alliance against the planters and the merchant-bankers – who played a major role in dispossessing white farmers due to their increased credit dependence. According to Post (Ibid):

The possibility of a populist coalition of Northern industrial workers and Southern black and white farmers in the 1880s and 1890s sparked a new planter counter- offensive, supported by Northern capital. Using the divisions between primarily African-American sharecroppers and mostly white cash-tenants, the planters and merchants imposed legal segregation of public facilities, disenfranchised African Americans and a substantial minority of poor whites through poll-taxes and literacy-tests, and maintained order in the plantation-districts through lynch-law and Klan-terror.

The imposition of Jim Crow laws and legal segregation in the 1890s once again created a legal structural basis for reproduction of racial ideologies. After the Civil Rights movement ended legal segregation, the economic inequalities, occupational and geographic segregation between black and white populations persisted to varying degrees.

Economic inequalities are self-reproducing under capitalism due to the dynamics of ‘real’ competition(Botwinick 2018), but their racial character is unique to the historical development of the state and the economy in the United States. The ideology of race does not persist because of the historical memory of slavery. It does so because the market allocates jobs, incomes and resources based on a racialized logic of market competition, hence reproducing the economic base for the ideology of racism.

Conclusions

The unique development of British North American colonial slavery emerged due to its development under a market dependent bourgeois state as opposed to a feudal absolutist state. A unique racial ideology developed under this system in order to explain the legal unfreedom of black slaves in a society that had formal equality and freedom, while in other colonies such ideology was not feasible both due to the absolutist nature of the states that did not promise formal equality or freedom and the large number of free blacks that would have contradicted such an ideology. British North American and later American racial slavery under capitalist market compulsion shaped the political, economic, and demographic structure of the US South. This provided the fertile terrain for persistence of racial inequality even in the absence of racialized slavery. As a result, so long as market competition continues to allocate economic resources in a racialized manner, the ideology of race will persist.

Works Cited

Acharya, Avidit, Matthew Blackwell, and Maya Sen. 2020. Deep Roots. Princeton University Press.

Allen, Kieran. 2004. Weber Sociologist of Empire. Ann Arbor, MI: Pluto Press.

Anderson, Perry. 2013. Lineages of the Absolutist State. Verso.

Baptist, Edward E. 2016. The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism. Basic Books.

Beckert, Sven. 2014. Empire of Cotton: A New History of Global Capitalism. Penguin Books Limited.

Blackburn, Robin. 1998. The Making of New World Slavery: From the Baroque to the Modern, 1492-1800. Verso.

Botwinick, Howard. 2018. Persistent Inequalities: Wage Disparity under Capitalist Competition. Brill.

Brenner, Robert. 1976. “Agrarian Class Structure and Economic Development in Pre-Industrial Europe.” Past & Present (70):30–75.

Brenner, Robert. 1985. “The Agrarian Roots of European Capitalism.” Pp. 213–328 in The Brenner Debate: Agrarian Class Structure and Economic Development in Pre-industrial Europe, Past and Present Publications, edited by C. H. E. Philpin and T. H. Aston. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fields, Barbara. 1990. “Slavery, Race and Ideology in the United States of America.” New Left Review 181:95–118.

Foucault, M., Mauro Bertani, A. I. Davidson, A. Fontana, F. Ewald, D. Macey, and Collège de France. 2003. “Society Must Be Defended”: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1975-1976. Allen Lane.

Historical Statistics of United States. 1970. “Historical Statistics of United States.” Retrieved December 17, 2020 (https://faculty.weber.edu/kmackay/statistics_on_slavery.htm).

Johnson, Cedric. 2019. “The Wages of Roediger: Why Three Decades of Whiteness Studies Has Not Produced the Left We Need.” Nonsite.Org. Retrieved December 15, 2020 (https://nonsite.org/the-wages-of-roediger-why-three-decades-of-whiteness-studies-has-not-produced-the-left-we-need/).

Johnson, Walter. 2013. River of Dark Dreams: Slavery and Empire in the Cotton Kingdom. Harvard University Press.

Lafrance, X., and C. Post. 2018. Case Studies in the Origins of Capitalism. Springer International Publishing.

Morgan, Edmund S. 2003. American Slavery, American Freedom. W. W. Norton & Company.

Patterson, Orlando. 1982. Slavery and Social Death. Harvard University Press.

Post, Charles. 2011. The American Road to Capitalism: Studies in Class-Structure, Economic Development and Political Conflict, 1620–1877. BRILL.

Post, Charles. 2017. “Slavery and the New History of Capitalism.” Catalyst. Retrieved December 14, 2020 (https://catalyst-journal.com/vol1/no1/slavery-capitalism-post).

Post, Charlie. 2017. “Comments on Roediger’s Class, Race and Marxism.” Salvage. Retrieved May 21, 2020 (https://salvage.zone/online-exclusive/comments-on-roedigers-class-race-and-marxism/).

Rioux, Sébastien, Genevieve LeBaron, and Peter J. Verovšek. 2020. “Capitalism and Unfree Labor: A Review of Marxist Perspectives on Modern Slavery.” Review of International Political Economy 27(3):709–31. doi: 10.1080/09692290.2019.1650094.

Shaikh, Anwar. 1990. “Capital as a Social Relation.” Pp. 72–78 in Marxian Economics, The New Palgrave, edited by J. Eatwell, M. Milgate, and P. Newman. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

The New York Times Magazine. 2019. “The 1619 Project (Published 2019).” The New York Times, August 14.

Weber, Max. 1988. The Agrarian Sociology of Ancient Civilizations. London ; New York: Verso.

Wesley, Charles H. 1932. “The Negro in the West Indies, Slavery and Freedom.” The Journal of Negro History 17(1):51–66. doi: 10.2307/2714675.

Wood, E. M. 2002. The Origin of Capitalism: A Longer View. London: Verso.

Wood, Ellen Meiksins. 1995. “Democracy against Capitalism: Renewing Historical Materialism.” Cambridge Core. Retrieved December 17, 2019 (/core/books/democracy-against-capitalism/0C87B28832394E438781BFDFBE8EDE42).

[*] See Weber’s (1988) conception of capitalism and its critique Allen (2004), also Wood (1995, 2002) for a critique of the so called “commercialization” model

[†] See Johnson (2019) for a critique of “whiteness” literature

[‡] See Patterson (1982)

[§] See Rioux, LeBaron, and Verovšek (2020) for a critique of Political Marxism.

[**] See Shaikh (1990) for a social definition of capital as opposed to a purely economic one.

[††] Nevertheless Blackburn (Ibid: 253) shows that the slave populations in Jamaica and Barbados grew significantly during the second half of the 17th century as British sugar plantations had experienced major expansions.